A kiss is a mischievous device — it can switch the human mind from doubt to hope, excitement to despair, and in a second trigger a shock of questions: Why did she kiss me? Why didn’t she? Why did he kiss me in that way? What if he had never kissed me that day, or in that place?

For lovers and potential lovers, even the most trivial meeting of lips can conjure powerful emotions and possibilities.

But how much should we read into a simple kiss? And can a kiss exist independent of nuance? After an encounter with a mysterious woman, Chekhov’s timid protagonist in The Kiss struggles to answer these questions and resolve the distinction between the significant and the meaningless in this most enigmatic of all human acts.

Plot summary

The Kiss opens on a May evening when the officers of the Reserve Artillery Brigade are invited to take tea at the manor house of a local aristocrat, Lieutenant-General Von Rabbek. At the house the General greets them, apologising that he cannot offer them rooms for the night due a large gathering of visiting family and neighbours. Together they take tea, brandy and cakes, and the General and his guests engage the officers in conversation, dance and billiards. Here we’re offered our first glimpse of the protagonist, Ryabovich: a “little officer in spectacles, with sloping shoulders, and whiskers links a lynx’s”.

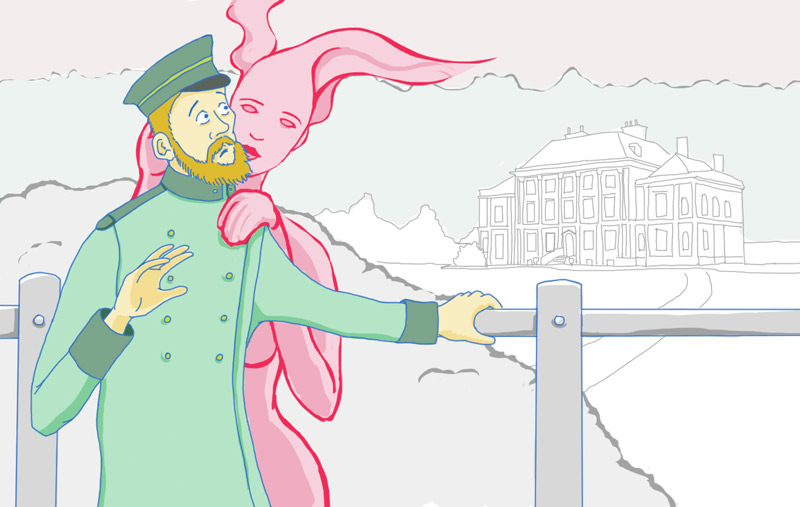

In this atmosphere of elegance and social sophistication Ryabovich is the “most ill at ease of them all”; unlike his companions, he is reserved, graceless, unskilled in conversation, and stands awkwardly at the periphery watching those around him enjoy themselves. During the evening, he takes a wrong turn while wandering about the halls and strays into a dark room. Moments later, two “unmistakably feminine arms” embrace his neck, and then, in the darkness, Ryabovich feels a kiss on his cheek. Realising her error, the mysterious woman shrieks and rushes from the room.

The encounter rouses Ryabovich’s spirit. He becomes intoxicated by the lingering smell of the woman’s perfume and the tingling sensation of her touch on his moustache; he forgets, just for a brief time, his undistinguished appearance and discards his inhibitions. He searches for the identity of his secret love, but in vain, and can only form a vague montage of her form based on the women who attended the evening. Nevertheless, the passion does not fade and the kiss begins to torment his days and nights with desire.

What is in a kiss?

Ryabovich is a typical tragic figure: an outsider trapped in a system ( in this case, the framework of late 19th century Russian society) he doesn’t understand. The aristocracy is declining after the emancipation of the serfs, yet their social conventions and much of the perceived prestige endures. Ryabovich, more at home with the mechanical routine of life in the regiment, is paralysed in such elegant settings. Plagued by insecurities about his appearance and behaviour, he cannot hope to ascend beyond his station alone — it takes one misfired act of affection from an upper class woman to reveal both the possibilities and impossibilities in his life.

When stripped of its emotional significance, a kiss is but an evanescent brush of lips on skin, a trivial meeting of mouths. It is something ordinary that occurs a million times a day, thousands of times a minute. Ryabovich understand this: “All I am dreaming about now, which seems to me so impossible and unearthly, is really quite an ordinary thing,” he says, freely admitting the coincidence of the event. But the promise of the extraordinary is too tempting for him to ignore and he eventually suspends his own logic. He comes to regard the kiss as an opportunity to thwart the future he once saw as predestined — of a mediocre life for a mediocre man, without love, without wealth and distinguishment— and relishes the thought that “something extraordinary, foolish, but joyful and delightful” has come into his life.

Like a drug, the kiss changes Ryabovich’s perception of the world: while under its influence, his familiar routine, the procession of the batteries, the horses, the canons, and every detail of his orderly and disciplined military life is rendered dull and inconsequential in comparison, and despite his best efforts to deny himself, he becomes intoxicated with his fantasies. To the inexperienced Ryabovich, the kiss assumes a meaning far greater than the physical act itself and he exaggerates and protracts its effects by wandering the camp behaving like a man in love. For example, he finds sudden solidarity with his love-struck comrades; after visiting a brothel, he is burdened by guilt and shamed at having betrayed the woman he loves; even the act of his morning wash arouses thoughts in him that there is “something warm and delightful in his life”.

Fate and other trivialities

While Ryabovich fantasises about love, the recognition of his own ordinariness keeps him tethered to reality. After each lapse of his imagination, his real self surfaces to remind him that the kiss was a mere triviality with little real meaning; something that occurs in the daily course of common life. Love, marriage, a fine home, he decides, are commonplace and that, given time, they will also come to him. As proof of this he notes the experiences of his married comrades. The realisation that what he is experiencing is therefore achievable and bound with that of the ordinary folk gives him courage to embellish his fantasies.

Still, his permission to fabricate results in self-delusion. The kiss arouses expectations and latent “dreams and fancies” too lofty for Ryabovich’s frail ego to handle. From what we learn of his character, although he possess the power to change his circumstances, the belief in his own inadequacy is so ingrained he is incapable of action. Indeed, the narrator suggests early on that Ryabovich suffers from “psychical blindness”: the inability to understand what is before one’s eyes. We cannot help but think however that, deep down, he comprehends the unattainability of love and believes it to be reserved exclusively for people such as the confident comrade Lobytko.

Our suspicions are confirmed when Ryabovich ventures to the house alone, hoping to find a further clue to his fate. When none appears, he capitulates. “How unintelligent it all is!” he exclaims, observing the General’s house from afar. His impotency exposed, he realises the futility of ever thinking that a kiss could have changed the course of his reality, and to him the world now seems an “unintelligible, aimless jest”.

Thoughts on ‘The Kiss’

The Kiss follows the theme of many of Chekhov’s short stories, in which a flawed and ordinary character is set up for existential disappointment. Chekhov allows Ryabovich a brief sample of the divine, only to, almost sadistically, deny him the possibility of ever retaining it. Like a small dog leaping for a treat that is just beyond it reach, Ryabovich is unable to control his desires and is powerless to change his condition.

What I think makes this story special is the simplicity with which it explores human desires and the yearning we all share for something bigger in our lives. Ryabovich’s wishes to better his circumstances are no different to our own; we can however, act upon opportunities and create new ones where none existed. The frustrating aspect of The Kiss is that we get the impression that no amount of good fortune will reverse the protagonist’s low self-esteem and stir him to action.

The Kiss acts as a microscope, zooming in on human emotion and the frailty of hope. Chekhov manages to creating a whole world around Ryabovich and the kiss, but does it so subtly we hardly notice it. The lines between the soldiers’ lives and that of the aristocrats is blurred and we wonder who wields the real power. General von Rabbek and his wife reveal openly that they have a social obligation to woo and maintain cordial relations with the military, but we get the impression that they are forced to show respect for classes of people with whom they might not have fraternised during former times. In this context, Ryabovich’s weaknesses appear unnecessary; that, his position as an office should grant him courage and the upper hand in dealings with the diminishing influence of the upper class. But character flaws run deeper; even in his uniform, Ryabovich is exposed as pathetic and incapable of taking control of his life.

Under Chekhov’s lens there is so much rich imagery that it would take many more pages to deconstruct. Details are used for for atmospheric effect: in the darkness, we smell the the spring fragrances, the perfumed oil of the kiss; we feel the young woman’s warm cheek and hear her hurried footsteps; as character markers: Ryabovich slouches and slopes around with his lynx-like whiskers, while his comrades glide and swagger. Details also highlight the juxtaposition of reality and fantasy: the exhaustive but mundane description of the brigade, with its strings of wagons, canons and harnesses is like a white-washed canvas on which Ryabovich paints his colourful dreams of love.

At the story’s end, we see our protagonist standing by the running river, pondering over the inexplicable meaning of the cycle of nature. Can he control his destiny more than a drop of water can control its way into the sea? Chekhov never promises more than his characters can give: we want Ryabovich return to the General’s, but somehow, we know not to expect the impossible from such a man.

All in all, even though it ends with hopelessness and disappointment, like an unexpected peck on the cheek, The Kiss leaves you with a feeling of having shared in Ryabovich’s desperation long after you’ve turned the page, and for this reason alone I consider it required reading for lovers of both Chekhov and the short story.

Read The Kiss by Anton Chekhov